On The Perils of Pattern Recognition

How Making Something Out Of Nothing Turns Nothing Into Something

My wife, a long suffering New York Giants fan, sent me this video of Daniel Jones throwing a pick six in today's pre-season game against the Texans.

Against my better judgment, I perused Twitter to see what people were saying about the play:

"DANIEL JONES IN HIS PRIME LMAOOOO"

"Jones is so bad, bro"

"Everyone who was in on the decision to pay Daniel Jones over Saquon Barkley needs to be fired"

As humans, we have an inextricable, biological imperative to seek patterns. In our earliest days, being able to quickly sort prey from predator, foe from friend and "yummy!" from "yo don't eat that, bro..." usually meant the difference between life and death. If you're here reading this, it's in some part a testament to your ancestor's pattern recognition. Kudos.

In broad strokes, this serves us better than not, but the billion dollar question looms over every data point:

Is the phenomena we observe part of a larger trend (something)? Or is it a singular data point in a sea of infinite data points (nothing)?

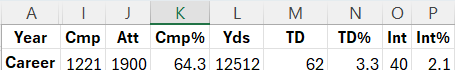

According to Pro Football Reference, Daniel Jones has attempted 1900 passes over the course of his career. 64% of them have found their intended target (1200). 3.3% of his attempts have resulted in a touchdown (62), while 2.1% have been interceptions (40)

In other words, if you look at DJ's entire career so far, on any given pass attempt, he is empirically more likely to throw a touchdown than an interception.

And yet that doesn't stop people from extrapolating what this interception - in a pre-season game, no less - "must mean" for his career, the Giants as an organization, and the judgment of the people who signed DJ "over" (interestingly implying a binary, mutually exclusive decision) a player at a different position.

All from one throw.

Alas, this article isn't about football; for what we have to discuss is much, MUCH more interesting.

Among the tools we have in our toolkit to disambiguate signal and noise, one stands out in particular: Statistical independence (or lack thereof, i.e: Statistical dependence).

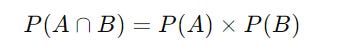

According to Robert Hogg in Introduction to Mathematical Statistics, a statistically independent event is one in which "the occurrence of one event has no effect on the probability of the occurrence of the other event". Think of flipping a coin - the probability of getting heads (50%) is the same no matter what occurred last.

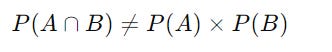

A statistically DEPENDENT event, on the other hand, is one in which "one event occurring is influenced by the occurrence of another event". If you're playing poker and two Aces hit the flop, that influences the probability of, say, a King getting drawn (because there are now two fewer cards in the deck).

If this was the end of our story, it would be a simple narrative indeed - To come back to Daniel Jones, every athlete knows about the importance of "having short memory", and logically, nobody would argue that one throw has absolutely anything to do with the next, much less confer to a singular data point predictive qualities over an entire career.

Clearly, we have an open and shut case of statistical independence.

Or do we?

Applications of statistical models to humans have always had questionable veracity. Football players are not coins, nor decks of cards, and sports media, forever extrapolating and grasping at straws to find meaning where there might not otherwise be any, will doubtless replay the error over and over. Pundits wringe their hands opining on what a statistically independent event "must mean" for the future. Such scrutiny can and does harm a player's confidence, and what in a vacuum may have been a statistically independent event, in the real world may well instead become a self-fulfilling prophesy.

For corroboration, we turn to a domain different but no less competitive - the stock market.

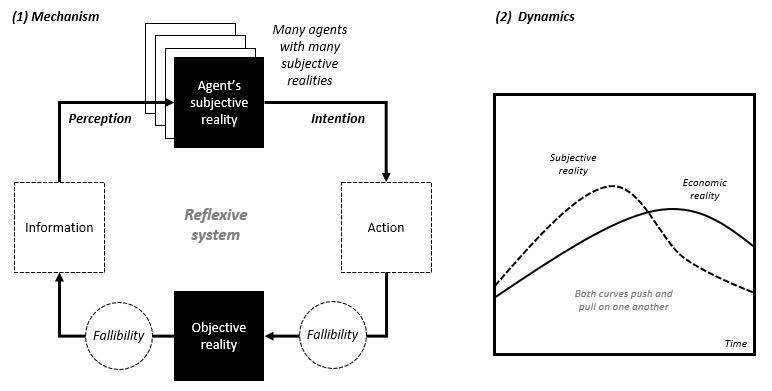

In "The Alchemy of Finance", George Soros explicates upon what he calls "The Theory Of Reflexivity", summarized by the following concepts:

Cognitive Function: Market participants form perceptions and make decisions based on their (Author's Note: definitionally limited) understanding of the market.

Manipulative Function: These decisions and actions, in turn, affect the market, which can reinforce the original perception.

Soros elaborates: "My conceptual framework, which I call reflexivity, holds that market participants are not merely passive observers but active agents whose decisions help shape the very reality they are observing."

In other words - objective information takes on meaning in the hands of subjective humans, and the actions they take based on their interpretation of information becomes a self fulfilling prophesy.

What's the point of all this and who cares?

In short, ascribing meaning to the information around us is a choice, and so too is the decision on whether the happenings of the world around us affect us positively or negatively. Armed with this power, one can begin to actively practice "Pronoia" - the belief that the Universe is out to do you good. We may never, nor should we ever, seek to eliminate the part of us that recognizes patterns, but in a sea of infinite data points we can make the choice to interpret information in a way that those patterns help guide us to take action in a way that betters our lives and those of the people around us.